Thực đơn

-

-

Câu hỏi thường gặp

- Cách nhận biết dăm trầm hương thật, tự nhiên hay trồng trọt

- Cách nhận biết hạt trầm hương giả phun/hấp dầu

- Làm thế nào để biết có nhiều hơn một loại dầu trong dầu của bạn

- Cách làm cho vòng tay bằng gỗ hoặc mala của bạn tối màu hơn

- Làm thế nào để nhận biết hạt Trầm hương có chìm mà KHÔNG chìm trong nước?

- Hương ngược hoạt động như thế nào và bạn đốt nó như thế nào?

- Bắt đầu từ đâu nếu bạn không biết trầm hương là gì?

- Tại sao bạn lại mất tiền nếu mua hạt giống và cây trồng?

- Nên chọn loại trầm hương nào?

- Các câu hỏi thường gặp

- Các bài viết liên quan đến trầm hương

- Đang chuyển hàng

-

CỬA HÀNG - Trầm hương

-

SHOP - Gỗ Thơm Khác

-

SHOP - Đế và Lư Hương

-

- Hướng dẫn sử dụng dầu Oud MIỄN PHÍ

- Lời chứng thực

- "Tại sao bạn lại mua cái này?"

- Liên hệ chúng tôi

- Về chúng tôi

- +61430284329

- Đăng nhập

-

Tiếng Việt

Mùi hương định hình nên một nền văn hóa: Câu chuyện về trầm hương ở Trung Quốc cổ đại

Tháng 4 13, 2025 6 đọc tối thiểu

Xin chào tất cả

Hôm nay, tôi đọc bài viết dưới đây của Feng.

Feng, LR (2024). Hương liệu nước ngoài, văn hóa khứu giác và sự sành mùi hương ở Trung Quốc cuối thời trung cổ . Tạp chí của Hội Hoàng gia Châu Á, 34(3), 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186323000640

Vì vậy, tôi nghĩ mình sẽ chia sẻ một số suy nghĩ và cũng làm một video dài 4 phút về vấn đề này.

Khi nói về Trung Quốc cổ đại, chúng ta thường nghĩ đến lụa, trà, thư pháp hay Vạn Lý Trường Thành. Nhưng có một khía cạnh lịch sử thường bị bỏ qua - mùi hương .

Hơn một nghìn năm trước, vào thời nhà Đường (618–907 SCN), một mùi hương đặc biệt đã du nhập vào Trung Quốc và âm thầm thay đổi mọi thứ: trầm hương .

Nó được vận chuyển bằng tàu biển như một loại hàng hóa thương mại thông thường, nhưng cuối cùng đã để lại dấu ấn sâu sắc trong văn hóa, tôn giáo, nghệ thuật và đời sống thường nhật của người Trung Quốc. Sau đây là lý do.

Trầm hương: Hương thơm “chìm đắm”

Trầm hương là một loại gỗ sẫm màu, thơm, hình thành khi một số cây bị nhiễm nấm mốc. Kết quả là một loại gỗ dày, giàu nhựa, có mùi thơm khó cưỡng - ngay cả trước khi bị đốt cháy.

Người Trung Quốc cổ đại gọi nó là chenxiang , có nghĩa là "hương thơm chìm" - vì nó thực sự chìm trong nước, không giống như gỗ thông thường.

Trầm hương không mọc ở Trung Quốc. Nó đến từ các khu rừng ở Việt Nam, Sumatra và các vùng khác ở Đông Nam Á. Các thương nhân vận chuyển nó bằng đường biển và đường bộ, cùng với các mặt hàng xa xỉ khác như ngọc trai, gia vị và trầm hương.

Mùi hương từ xa

Trước khi trầm hương xuất hiện, người Trung Quốc chủ yếu sử dụng các loại cây địa phương để tạo mùi hương - chẳng hạn như ngải cứu, tiêu Tứ Xuyên và các loại thảo mộc thơm. Những mùi hương này rất quen thuộc và được sử dụng trong các nghi lễ, y học và đời sống hàng ngày.

Nhưng mọi thứ bắt đầu thay đổi khi những mùi hương mới từ nước ngoài du nhập vào:

-

Nhũ hương từ Ả Rập

-

Gỗ đàn hương từ Ấn Độ

-

Xạ hương từ Tây Tạng

-

Và tất nhiên, trầm hương từ Đông Nam Á

Đây không chỉ là những mùi hương dễ chịu. Chúng nồng nàn, phức tạp và khác hẳn với bất kỳ mùi hương nào người dân địa phương từng trải nghiệm trước đây.

Đặc biệt, trầm hương nổi bật. Nó đậm đà, êm dịu và thậm chí còn mang tính tâm linh. Khi đốt, nó lan tỏa trong không khí một mùi hương ấm áp, sâu lắng, có thể thay đổi toàn bộ bầu không khí.

Từ xa xỉ đến phong cách sống

Lúc đầu, trầm hương được dùng để thể hiện sự giàu có và quyền lực.

Các hoàng đế đốt nó trong những bữa tiệc xa hoa. Các thương gia giàu có thì phủ đầy nhà mình bằng khói hương của nó. Chỉ riêng việc sở hữu nó đã là một biểu tượng địa vị.

Nhưng theo thời gian, mọi người bắt đầu sử dụng nó theo những cách chu đáo hơn.

Trong giới học giả, nhà sư và quý tộc, một nền văn hóa mới bắt đầu hình thành. Thay vì đốt nhang để trưng bày, họ bắt đầu nghiên cứu hương thơm - cách các mùi hương khác nhau hòa quyện, cách chúng phù hợp với từng mùa, từng tâm trạng, hay thậm chí là từng loài hoa.

Nó đã trở thành một loại hình nghệ thuật . Người ta tổ chức các cuộc thi hương . Họ sáng tác thơ về mùi hương. Họ thảo luận xem mùi hương nào phù hợp nhất với những bối cảnh nhất định - chẳng hạn như tiệc trà, dạo vườn, hay thiền định.

Trầm hương không còn chỉ là một thứ xa xỉ nữa. Nó đã trở thành một phần trong cuộc sống thường nhật của giới thượng lưu.

Gặp gỡ Não Rồng (龍腦): Họ hàng thơm của Trầm hương

Một mùi hương hiếm khác vào thời đó được gọi là Long Não , hay Long Não trong tiếng Trung. Ngày nay, chúng ta gọi nó là long não .

Long Não có nguồn gốc từ cây long não ở những nơi như Borneo. Nó có mùi hăng, mát và được sử dụng chủ yếu trong y học, nghi lễ, và đôi khi trong thực phẩm. Nó mạnh mẽ nhưng rất đặc trưng.

So với trầm hương, Não Rồng có tính chính xác và hạn chế hơn về cách sử dụng.

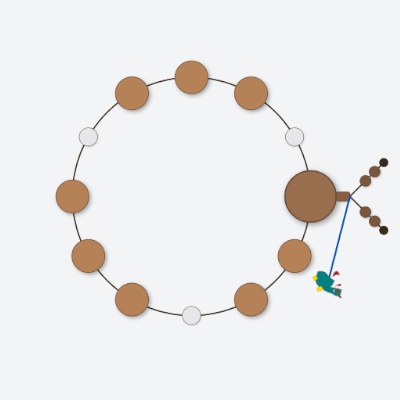

Quả cầu trầm hương và long não

Ngược lại, trầm hương có ở khắp mọi nơi—

-

Bị đốt cháy trong các ngôi đền

-

Pha trộn vào hương

-

Được chạm khắc thành các bức tượng tôn giáo

-

Ngay cả khi ngâm trong rượu và mặc trong quần áo

Cả hai đều hiếm. Cả hai đều được nhập khẩu. Nhưng trầm hương có ảnh hưởng văn hóa lớn hơn.

Không có quy tắc, không có giới hạn

Điều thú vị là vào thời nhà Đường, mọi thứ đều có quy định - quần áo, lụa là, thậm chí cả ngói lợp - nhưng lại không có quy định nào về hương .

Điều đó có nghĩa là bất kỳ ai đủ giàu đều có thể mua và đốt bao nhiêu tùy thích.

Một số người sử dụng trầm hương một cách cẩn thận và tao nhã. Những người khác đốt nó với số lượng lớn chỉ để khoe khoang. Thậm chí còn có những câu chuyện về cướp biển đốt những đống trầm hương như thể chúng là sáp nến.

Các quan chức đôi khi chỉ trích người giàu vì sự phung phí. Nhưng không ai có thể ngăn chặn được. Hương thơm thì miễn phí — không phải về mặt pháp lý hay tài chính, mà là về mặt văn hóa. Nó trôi dạt đến bất cứ nơi nào người ta muốn.

Khói thiêng

Ngoài đời sống thường ngày, trầm hương còn có mối liên hệ mật thiết với tôn giáo.

Trong các ngôi chùa Phật giáo, nó được dùng để thanh tẩy không gian và xoa dịu tâm trí. Trong các nghi lễ hàng ngày, nó đánh dấu những khoảnh khắc quan trọng của cuộc đời - sinh nở, tang lễ, thiền định, cầu nguyện.

Khi các nhà khảo cổ mở hầm mộ nghìn năm tuổi tại chùa Famensi, họ tìm thấy những chiếc lư hương vẫn còn chứa đầy trầm hương và gỗ đàn hương, được bảo quản cẩn thận với nhãn mác. Đó chính là sự linh thiêng của nó.

Không chỉ là mùi hương dễ chịu. Mà còn là sự hiện diện về mặt tâm linh.

Hương thơm sống trong những câu chuyện

Chúng ta không có sách hướng dẫn từ thời nhà Đường giải thích cách người ta sử dụng hương. Nhưng chúng ta có những câu chuyện kể.

Trong một câu chuyện, chiếc khăn quàng cổ của một nàng công chúa - được ướp hương Não Rồng - vô tình bị nhặt mất. Nhiều năm sau, mùi hương ấy khơi dậy một dòng ký ức dâng trào trong hoàng đế, gợi nhớ về nàng sau khi nàng đã khuất bóng.

Trong một trường hợp khác, một chiếc áo choàng thơm phức được đưa đến một cửa hàng rượu, và mọi người sửng sốt vì mùi hương vẫn còn nồng nàn đến vậy. Họ nhận ra mùi hương đó là thứ mà chỉ hoàng gia mới có thể mặc.

Những câu chuyện này cho thấy mùi hương mạnh mẽ đến nhường nào - không chỉ về mặt thể chất mà còn về mặt cảm xúc. Nó kết nối con người, địa điểm và ký ức.

Từ hàng hóa đến văn hóa

Trầm hương được đưa đến Trung Quốc bằng tàu thủy - đóng gói trong thùng, mua và bán giống như bất kỳ mặt hàng xa xỉ nào khác.

Nhưng nó không chỉ đơn thuần là một sản phẩm.

Nó đã trở thành một phần của văn hóa Trung Hoa và giúp định hình quan niệm của con người về cái đẹp, nghi lễ, cảm xúc và thậm chí cả thời gian.

Từ các trò chơi hương đến các ngôi đền linh thiêng, từ những câu chuyện viết tay đến những con tàu đắm vẫn còn mang theo mùi hương, hành trình của trầm hương không chỉ là hương thơm.

Vấn đề là ở ý nghĩa.

Và hơn một nghìn năm sau, ý nghĩa đó vẫn còn tồn tại.

Bạn có tò mò về Trầm hương nhưng chưa thử? Hãy thử một số miếng Trầm hương của chúng tôi ngay hôm nay.

Để lại một bình luận

Bình luận sẽ được duyệt trước khi hiển thị.

Cũng trong Tin tức

The Eight Major Components of a Traditional Prayer Bracelet

Tháng 11 22, 2025 8 đọc tối thiểu