| Religion / Tradition | Event | Calendar Type | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | Vesak, Ullambana | Lunar Calendar | Vesak is celebrated on the full moon of the Vesak month, and Ullambana (Ghost Festival) is on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month. Both depend on the lunar cycle, so dates change yearly. |

| Hinduism | Diwali, Navaratri, Daily Puja | Lunar Calendar | Most Hindu festivals follow the Hindu lunisolar calendar. Diwali falls on the new moon of Kartika, and Navaratri begins on the new moon or full moon depending on the region. |

| Taoism / Chinese Traditions | Chinese New Year, Qingming, Ghost Festival | Lunisolar Calendar | Chinese New Year begins on the first new moon between 21 January and 20 February. Ghost Festival occurs on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month. Qingming is an exception because it follows the solar calendar (around 4 or 5 April each year). |

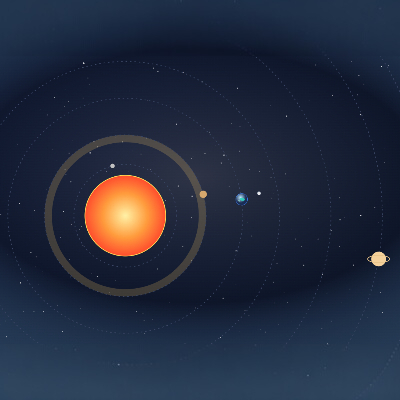

| Christianity | Easter, Christmas, High Mass | Solar and Lunar (Hybrid) | Christmas follows the fixed solar date (25 December). Easter is calculated based on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the March equinox, so it varies each year. |

| Islam | Friday Jumu’ah, Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha | Lunar Calendar | The Islamic calendar is purely lunar. Each month begins with the sighting of the new moon. Therefore, Eid dates move about 10 to 11 days earlier each year in the Gregorian calendar. |

| Shinto | New Year (Shogatsu), Obon, Matsuri | Solar Calendar (with Regional Variation) | New Year follows the solar calendar (1 to 3 January). Obon can follow either the solar or lunar calendar, depending on the region (usually mid-August). Local Matsuri follow the solar calendar but may have lunar roots. |

| Confucianism | Ancestor Worship (Qingming and September Ceremonies) | Solar Calendar | Qingming is tied to the solar term (around 4 or 5 April). Autumn ancestor worship in September is fixed by solar timing. |

| Indigenous Traditions | Harvest and Healing Rituals | Lunar and Seasonal (Varies) | Many indigenous ceremonies follow natural cycles such as moon phases, seasons, or harvest periods rather than formal calendars. |

| Baha’i Faith | Nineteen-Day Feast | Solar Calendar | The Baha’i calendar is solar, consisting of 19 months of 19 days each. Feasts occur every 19 days. |

Buddhism

Vesak (Buddha’s Birthday) – May

Vesak marks the birth, enlightenment, and passing of the Buddha. Temples are adorned with flowers, lanterns, and incense burners. The burning of sandalwood and agarwood purifies the environment and symbolises inner clarity and detachment from worldly desires.

Ullambana (Ghost Festival) – July or August

During Ullambana, Buddhists offer food and incense to aid ancestors and wandering spirits. The soothing aroma of agarwood and sandalwood is believed to comfort the souls and guide them towards peace. The festival is based on a story from the Ullambana Sutra where the Buddha instructed Maudgalyayana on how to save his deceased mother from a life of torment by making offerings to the Sangha.

Daily Offerings – Year-round

Monks and lay practitioners light incense each morning and evening as an offering to the Buddha and bodhisattvas. The fragrance represents mindfulness and the impermanence of life.

Hinduism: Fragrance as a Divine Offering

Daily Puja – Year-round

In Hindu households and temples, incense is part of daily worship (puja). The rising smoke is believed to carry prayers to the heavens, inviting divine presence and blessing.

Navaratri – March–April and September–October

This nine-night festival honours the Goddess Durga. Incense and agarwood are burned to purify the atmosphere and to represent devotion and energy (shakti).

Diwali – October or November

The festival of lights celebrates the triumph of good over evil. Before lighting lamps, devotees cleanse their homes with fragrant smoke from agarwood and camphor, symbolising the removal of negativity and ignorance.

Taoism and Chinese Traditions: Fragrance for Harmony

Chinese New Year and Ancestral Worship – January or February

Families light incense sticks at home altars and temples to invite prosperity and harmony in the new year. Agarwood and sandalwood coils fill the air with auspicious scent to honour both gods and ancestors.

Qingming Festival – April

Also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day, this event honours ancestors by visiting graves and offering food, flowers, and incense. The smoke connects the living and the departed in spiritual remembrance.

Ghost Festival (Zhongyuan Jie) – July or August

During this seventh lunar month festival, incense and paper offerings are burned to comfort wandering spirits, ensuring they do not bring misfortune to the living.

Christianity: Prayers Rising Like Smoke

Easter Vigil – March or April

On the holiest night of the Christian calendar, frankincense and myrrh are burned to sanctify the church and symbolise the prayers of the faithful ascending to Heaven.

High Mass – Year-round

During solemn services, the priest swings a censer filled with burning incense around the altar and congregation. The aroma purifies and prepares the hearts of worshippers for the sacred mystery of the Eucharist.

Christmas Midnight Mass – 24–25 December

At this joyous celebration of Christ’s birth, incense recalls the gifts of the Magi: gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and represents reverence and thanksgiving.

Islamic Traditions: The Purity of Oud

Friday Jumu’ah – Weekly

In many Muslim communities, mosques are perfumed with oud (agarwood) or bakhoor before the Friday congregational prayer. The fragrance signifies cleanliness, beauty, and respect for the house of worship.

Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha – Dates Vary

During these festivals, oud and amber blends are burned in homes and mosques. The smoke symbolises joy, renewal, and gratitude after a period of devotion and sacrifice.

Sufi Dhikr Ceremonies – Year-round

In Sufi gatherings, the rhythmic recitation of divine names (dhikr) is accompanied by the burning of agarwood to elevate the spiritual atmosphere and inspire inner peace.

Shinto: Purifying the Spirit through Scent

New Year (Shogatsu) – 1–3 January

Shinto priests burn Japanese incense (koh) and agarwood (jinkō) to cleanse shrines and invite blessings from the kami (spirits) for the year ahead.

Obon Festival – August

Families honour their ancestors by lighting incense and lanterns, guiding ancestral spirits back to the world of the living for a brief reunion.

Shrine Festivals (Matsuri) – Year-round

Incense is burned as part of purification rituals, allowing participants to enter sacred space with a clear mind and heart.

Confucianism: Reverence for Ancestors

Ancestor Worship Ceremonies – April and September

Incense plays a central role in Confucian ancestral rites. Burning agarwood or sandalwood before ancestral tablets signifies respect, gratitude, and the continuity of family lineage.

Indigenous and Animist Traditions: Fragrance of the Earth

Across Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, indigenous peoples use smoke from aromatic resins and agarwood in healing, initiation, and harvest ceremonies. The scent connects them to nature, ancestors, and the spirits that dwell within the land.

In Australia, First Nations people also burn "incense". The smoking ceremony is a deeply significant and ancient custom for many First Nations peoples across Australia. It is a traditional ritual of purification and cleansing, where native plants, like eucalyptus, emu bush, or other local botanicals are smouldered to produce a fragrant smoke. This smoke is believed to have spiritual and physical cleansing properties, used to ward off bad spirits, heal, and cleanse a space or people. It is commonly performed as part of a Welcome to Country, signifying a welcome and acknowledging the ancestors and their connection to that land

Baha’i Faith: Unity and Purity

Nineteen-Day Feast – Every 19 Days

In the Baha’i tradition, gatherings for prayer and consultation are sometimes accompanied by the burning of gentle incense or aromatic wood. The fragrance represents spiritual purity and the unity of humankind.

A Universal Language of Fragrance

Though separated by geography, culture, and belief, the ritual use of incense and agarwood reveals a shared spiritual instinct to reach beyond the physical world through the language of fragrance. From Buddhist temples to Christian cathedrals, from Hindu shrines to Islamic mosques, the curling smoke reminds humanity of something timeless: that true devotion, like fragrance, transcends all boundaries.